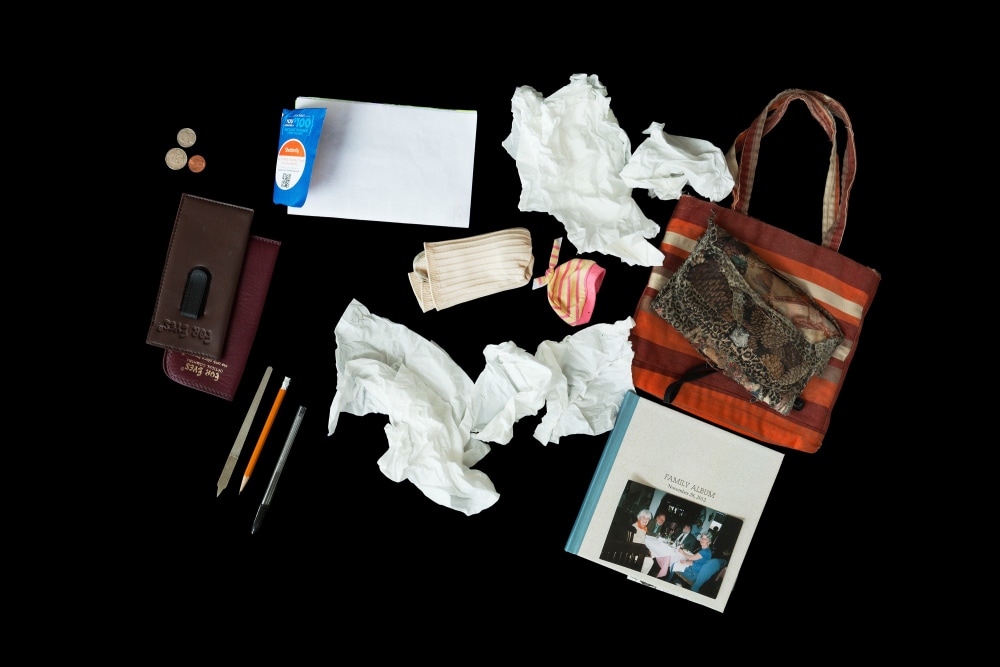

Kija Lucas, November 18, 2013, 2015. Archival pigment print, 20 x 30 inches.

We asked photographer Kija Lucas to share some insights on her collaborative process and specifically the work from her series, Collections from Sundown which are part of our current exhibition Documents. She explains how she considers her work similar to scientific inquiry, the significance of portraits and her relationship with her Grandmother, whom the series is about.

GAG: You generally work in series - as a form of documenting or cataloging objects that have emotional significance, either for yourself or others. What lead you to this format?

Kija Lucas: I have a deep desire to know people, to really understand my-self and others. I want to know what drives us. I want to know how we become who we are, as individuals and as a collective. There is so much scholarship that goes into these inquiries, but I feel it is often disconnected. I think as an artist, I have the luxury of not having to feign objectivity. I can create works that use the visual tropes of objectivity, but keep the humanity at the forefront.

GAG: Your photographs are formal in their presentation, though intimate in their subject. How do you see this contrast?

KL: I find the formal aspects of scientific photography, the idea of a mechanical eye and objectivity to be fascinating. Photography is something that we learn to trust, to be truth, however it is completely influenced by whoever is behind the camera, and the person behind the camera is influenced by life experience, so how do we discern truth? The re-contextualizing or isolation of the objects gives the illusion of objectivity, and the deeply intimate nature of the object itself, I like to think, creates a more personal connection with the viewer. If you see the note on the kitchen table or dresser where it was left, it becomes a thing that is in a place that we can perhaps identify with, but it is further away, the experience of another. If the object is isolated, or with other objects, but not part of a scene, we are able to see it as if it is here, as if we can know something about it.

GAG: In past series you’ve done, there has been a research aspect or process of collecting and collaborating. Is that communal function important to your work? Is there is an educational aspect to what you do?

KL: I think that the communal aspect is important to a lot of my work, but at the same time I often work in isolation. I think the transition to photographing while I am with others while at first difficult, was incredibly helpful for me. I learned how to ask a stranger, a loved one, an acquaintance for something incredibly intimate, I learned how to be present and out of my own head, to listen. I am incredibly thankful for the kindness of others, which is the only way I can be an artist or survive the day.

GAG: The work we’re showing, from “Collections from Sundown” is specifically about your grandmother and her illness. Do you think there is a collaborative aspect to choosing the objects you photograph? How much of the process and resulting photographs do you feel are about your relationship with her?

KL: I do feel that this work is a collaboration with my Grandmother. I would not have been able to make it without her. I wanted to try and understand her new reality, knowing it is fully impossible to do so. The closest I could get are these arrangements that are failing at a real sense of organization or understanding. I am using her objects, and her words, trying to re-create my understanding of how she is seeing things, and how it is to be in conversation with her. The work is very much about my relationship with her, but more of a trying to find the her that she was, while trying to respect who she was as her disease progressed, and not trying to force an impossible return to shared reality.

GAG: Alzheimer’s - and mental illness generally - change one’s perception of reality; your work from this series show this well, but also the evolution of the disease over time. The series covers years, has your understanding of what you’re doing evolved over time?

KL: Yes, definitely. The work started with photographing the objects she collected or packed. I would ask my mother to make pictures with her phone of these items, and when I would visit, I would re-stage them to make the photographs. I also asked her to save the notes, not knowing what I would do with them. When my Grandmother had caretakers with her more often, she stopped packing as much, and I began trying to wrap my head around this decade of notes. I would try and organize and arrange them. And no matter how many arrangements and photographs I made, I never really felt done. I would wait a while and try again. Eventually, about six months after her death, I decided to give myself one more try at the work, seeing if there was anything left unsaid, anything else that needed to be included. I decided at that point that I needed to call the body of work finished, in order to mourn her. I think that is something important that I learned. Letting go is hard, letting go of loved ones, letting go of our formed ideas of who they are.

GAG: It’s hard not to see your work as somewhere between portraits and still-lives, where on this spectrum do you see it, or do you?

KL: I think it is smack dab in the middle. I haven't photographed a person as part of my work since my first semester of grad school (2008), but I think my work is still very much about people. The objects represent their owners. Even the botanical work in, In Search of Home, is about humanity and the creation of race, how that specifically affected my ancestors, and my immediate family, and more broadly every system in the United States. I think I shifted toward still lives, because I was questioning what it meant to photograph another person, and if that was the best way to represent them. Even though you don't see people in my work, they are why and what the work is created for.

See more of Kija's work in Documents.