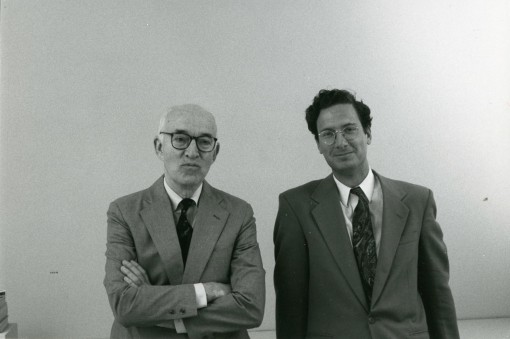

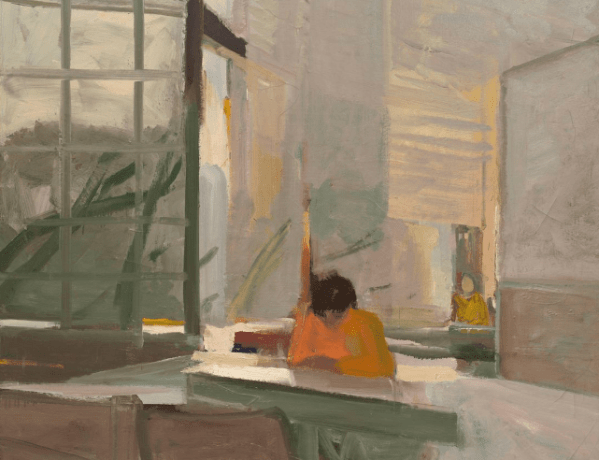

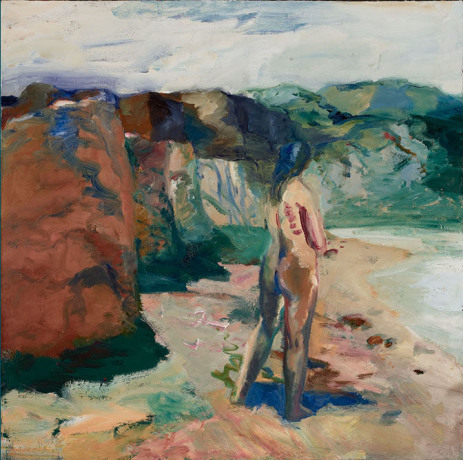

Elmer Bischoff (1916-1991) is perhaps best known as a founder, along with Richard Diebenkorn and David Park, of the Bay Area Figuration, the painting style that emerged in San Francisco in the early 1950s, which combined the gestural immediacy of abstract expressionism, with a narrative subject matter. Born and raised in Berkeley, CA, Bischoff showed interest in art from a young age. He enrolled at the University of California, Berkeley as an art major, studying with professors such as Erle Loran and Margaret Peterson who would influence not only his approach to painting, but also to teaching. He went on to receive his MFA from Berkeley, though his early career as an artist was cut short by the entry of the United States into WWII. Bischoff enlisted as an officer in the Air Force in 1941 and served until 1945 - a period during which he could make art only intermittently but nonetheless had a profound effect on him.

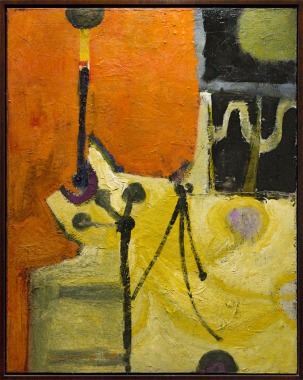

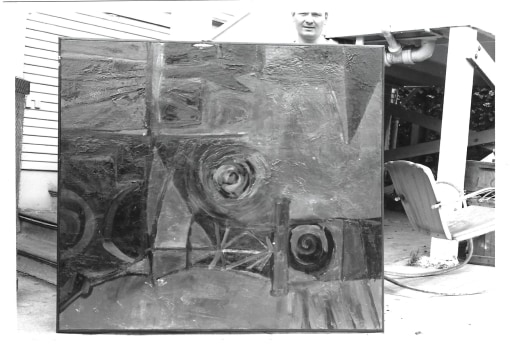

As was the case for many of his colleagues, Bischoff returned to art and teaching when he was offered a position at the California School of Fine Arts in 1946. Among those on staff at the school were David Park, Hassel Smith and Clyfford Still, all of whom, Bischoff included, would have a major impact on art in the Bay Area, through both the paintings they were making and the students they taught. Already artists were moving away from the European-style, cubist mode that was prevalent up to then, particularly in reaction to recent paintings by Pollock and Rothko exhibited at the San Francisco Museum of Fine Art. Bischoff was no exception and fully embraced this new approach to painting - incorporating his existing interest in metaphysical thought and ancient art. Bischoff soon began working closely with Park, Smith and Richard Diebenkorn, whose studios were adjacent to his in downtown San Francisco and who shared his love of jazz. Their camaraderie and democratic approach to painting is evident in the similarities and shared vocabularies of the paintings they made. Stylistically the paint became thicker, freer, more gestural and less structured than it had been before, completely eschewing the figurative aspect in favor of blocks of color and calligraphic lines. In Bischoff’s case, he had reached what could be described as a synthesis of the automatism of surrealism, the heavy, ugly paintwork of Still with the new lyrical gesture he was developing along with his contemporaries.

A 1948 exhibition at SFMFA of new paintings by Park, Bischoff and Smith was a turning point; critics for the New York Times called it “first sensation painting” and recognized that “a fruitful direction may emerge for San Francisco art.” In many ways the genesis of the muscular abstraction shown in 1948 was reactionary: against commercialism, the formulaic-ness of surreal painting, and the cult of personality imposed by Still. In part due to his increasingly collaborative relationship with Park and others, Bischoff’s paintings had become so bold, so radical that in another review of the exhibition, the new paintings were deemed a “complete release from restraints of all kinds.” Ironically, for all the radical appearance of the work, within a matter of years it had become a dominant mode of painting in the Bay Area, pushing first Park, then Bischoff back to figuration in 1952.

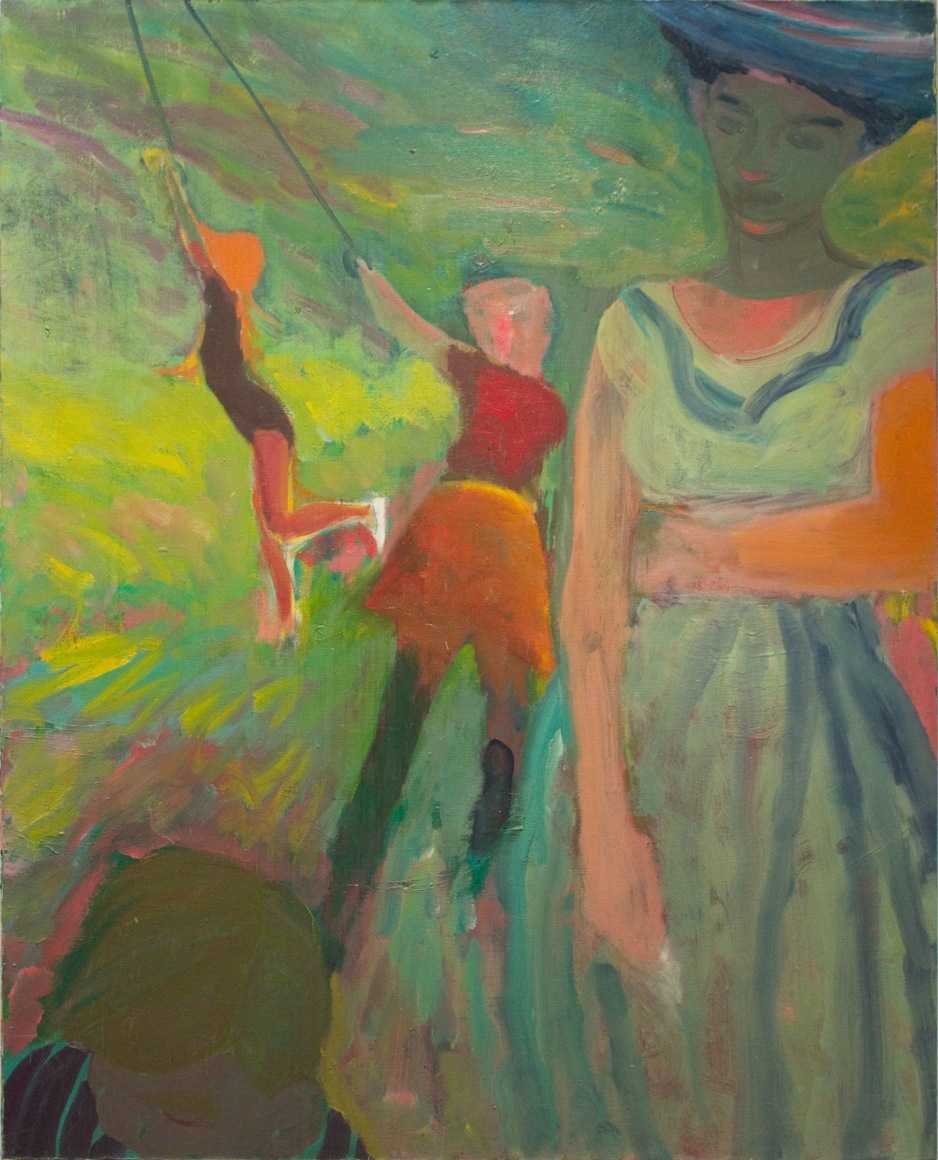

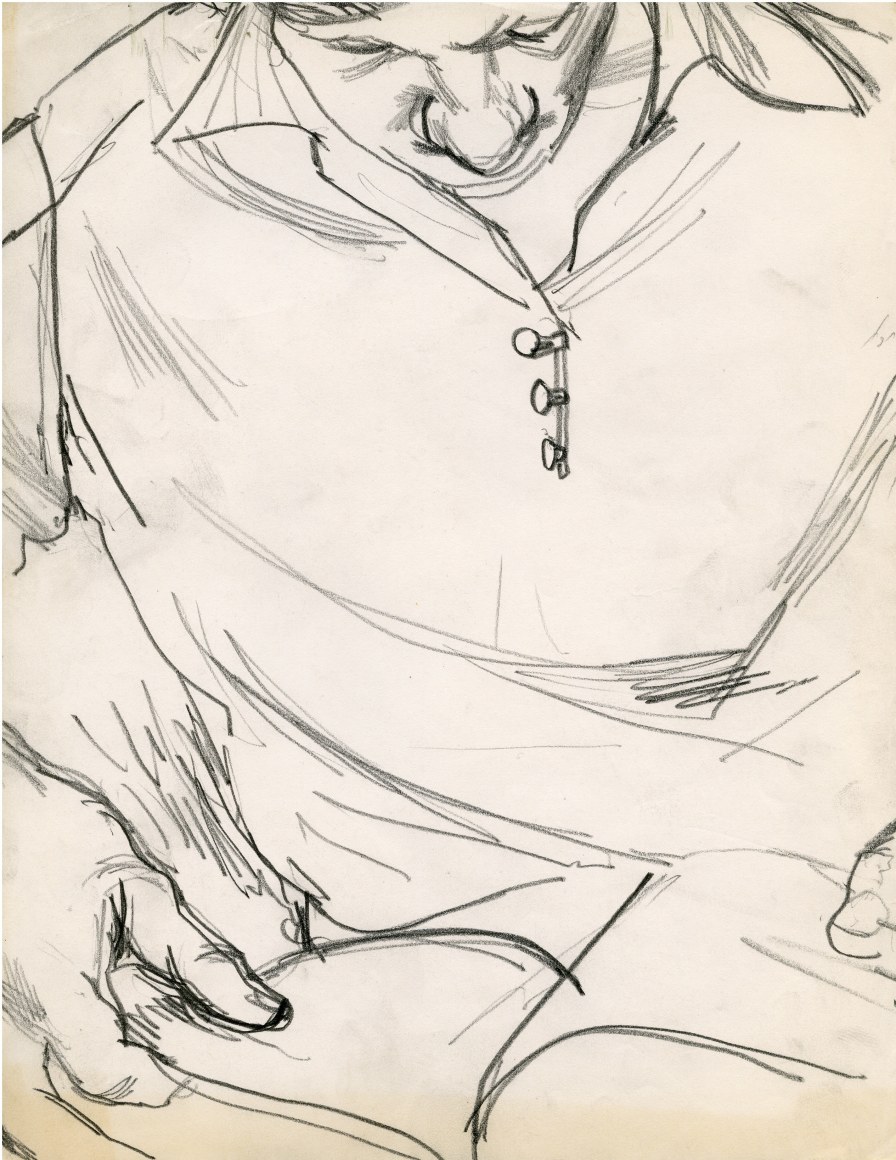

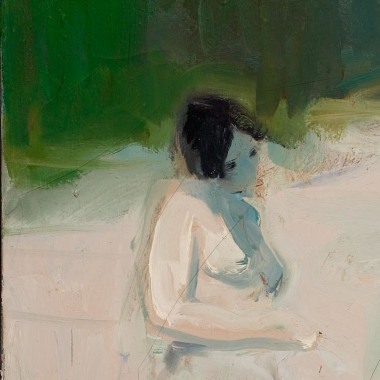

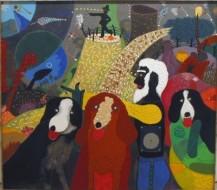

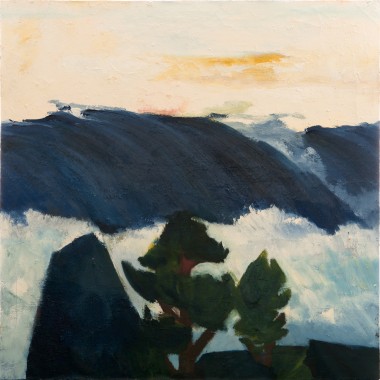

In 1952, Bischoff left teaching at CSFA and took a position in rural Marysville, California. Though isolated, he continued to develop his figurative style, drawing inspiration from the domestic and pastoral scenes which surrounded him. Upon returning to San Francisco and CSFA in 1956, he took a studio space on Montgomery Block - known as ‘Monkey’ Block - where he, with Park, Diebenkorn and others began meeting for regular figure drawing sessions. The following year the Oakland Art Museum held the first exhibition of what became known as Bay Area Figuration, including paintings by Bischoff, Park and Diebenkorn, along with their colleagues and studio neighbors, Paul Wonner, James Weeks and others. This exhibition in large part lead to Bischoff’s commercial success, drawing the attention of New York dealer George Staempfli, who gave him his first solo exhibition in NY in 1960. For the next twelve years, Bischoff continued to work figuratively with the same lush, painterly style of his earlier abstractions. He increasingly drew from visual memory in composing his pictures, and while quotidian settings - interiors landscapes - continued to be a theme, they are intentionally unspecific, as are his figures. By the late ‘60s the paintings had become atmospheric and brooding, veering into the allegorical. In 1975, the Oakland Museum hosted his first museum retrospective, of figurative paintings, though by then Bischoff had made a permanent shift back to abstraction. His late abstractions are characterized by active, geometric shapes set in hazy, painterly grounds and retain much of the lyricism which defined his career. Bischoff retired from teaching in 1985, having left CSFA for his alma mater, UC Berkeley in 1963. He continued to paint up to his death, of cancer, in 1991.

Bischoff exhibited widely throughout his career and was recognized by inclusion in seminal museum exhibitions during his lifetime. His work is represented in major museum collections across the country, including the Museum of Modern Art, New York; San Francisco Museum of Modern Art; the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston; the Philips Collection, Washington DC; Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden, Washington DC; Orange County Museum of Art, Santa Ana and the Whitney Museum of American Art, New York; among others. He has been the subject of multiple retrospective exhibitions, two organized by the Oakland Museum, California, in 1975 and 2001, and one organized by the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art in 1985.